Gambling and Development: The Case of Djakarta's "flower organization"

by Donald K. Emmerson in Asia 27 Fall 1972 page:19-36

An article about politics in Indonesia in the 60's, with lots of details about how the game was played and organized in Djakarta.

|

Pairs

| | 12 horse | | |

| 19 butterfly | | 26 dragon | |

| | | | |

| | 28 ?cock | | |

| 36 fox | 4 pheasant | 8 tiger | 21 swallow | 34 deer |

| 27 turtle | 10 centipede | 7 pig | 11 dog? | 25 vulture |

| 3 goose | | 6 rabbit | | 32 snake |

| 2 shellfish | | 35 goat | | 17 stork |

| | 31 ?lobster | | 23 ?monkey |

| | | | 33 spider |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | | 18 cat | |

| | | 24 ?frog | |

| | | 16 bee | |

| | | | |

| 1 whitefish | 5 ?earthworm |

| 20 ?jewel |

| 9 ?ox |

| 15 ?rat |

| 13 elephant | 14 ?wild cat |

| 22 ??pigeon |

| 30 - carp |

| 29 eel |

|

Pairs

| 1 whitefish | 5 earthworm |

| 2 shellfish | 16 bee |

| 3 goose | 32 snake |

| 4 pheasant | 12 horse |

| 6 rabbit | 20 jewel |

| 7 pig | 24 frog |

| 8 tiger | 17 stork |

| 9 ox | 33 spider |

| 10 centipede | 18 cat |

| 11 dog | 15 rat |

| 13 elephant | 14 wild cat |

| 19 butterfly | 27 turtle |

| 21 swallow | 22 pigeon |

| 23 monkey | 30 carp |

| 25 vulture | 35 goat |

| 26 dragon | 31 lobster |

| 28 cock | 29 eel |

| 34 deer | 36 fox |

|

butterfly-19-general-right ear

dragon-26-king-left ear

fish-1-devil

elephant-13

fish-29-priest

fish-30-sailor

bee-16

fox-36-nun

[[[[p19]]]]

It is fashionable these days among American political scientists to ask of a Third World country like Indonesia not "How democratic is your government?" but "How effectively does it govern?"

This shift in scholarly interest from form to performance has been paralleled by larger events,

notably the bloody thwarting of American idealism in South Viet Nam, which we could not make safe for democracy after all.

And if I may reappropriate Harry Benda to the ranks of political science, he was among the first to articulate this kind of realism about the export potential of democracy, not merely on his many fruitless journeys to Washington to try to talk sense with American policy-makers about Southeast Asia, but in his writings as well.

[[[[p20]]]

[[[[p21]]]

of legitimacy gained in a partially coerced election is a separate question and serves to remind us that although we can distinguish a government's form and performance in theory, they are related in practice.)

Aside from the logical precedence of extraction as a priority task, there is also a precedence in the Indonesian case of an economic before a political task.

Economic investment in the oil fields yielded revenue, part of which was redirected into political investment in an election.

The resource of legitimacy gained in the election (where coerced voting may at least have further conditioned the political reflex to conform) is now being reinvested in a campaign for wider citizen compliance with extractive tax laws, for example.

Any increased tax revenues may then become available for reinvestment in other domains, and the process can repeat itself indefinitely.

From this perspective, strengthened governmental capacity is a product of rising successive yield-to-investment ratios.

Although the process itself is unrelated to form, occurring in mobilizing and nonmobilizing states alike, it is characteristic of mobilizing states, like Mao's China, that they intialize the extraction of political resources for reinvestment where nonmobilizing regimes like Soeharto's Indonesia prefer to generate the capacity-enhancing process by pulling first the economic lever, often with substantial outside help.

This raises another difference between "soft" and "hard" states, not merely that the former are more incapacious than the latter but that the extractive priorities of the former differ as well. The dilemma they face is the same, but they respond to it differently. The dilemma is that in order to extract more resources one has to develop the capacity to do so, but in order to develop that capacity one has to extract more resources.

The sensible way to break out of this circular bind is to find those kinds of resources that can be extracted most easily, that is, to maximize initial yield-to-investment ratios so that governmental capacity can be strengthened as much as possible as soon as possible for future reinvestment.

A mobilizing

[[[[p22]]]

regime is by definition an organizer of human resources, especially in the form of support for the "correct" political line; reshaping the economic behavior of large peasant populations is a more difficult (i.e., costlier) task.

But a non-mobilizing regime, again by definition, finds even political mobilization difficult.

For a non- mobilizing regime the highest yield-to-investment ratios can be gained from outside extractive investment in material resources.

High-value minerals exploited by a foreign firm can generate a torrent of public revenue without inconveniencing a single citizen.

Caltex and the thoughts of Chairman Mao become functional equivalents. The discussion so far has been extremely simplified.

Regimes, obviously, do not choose between extracting human versus material, or political versus economic, resources as if these were mutually exclusive alternatives. Instead, they typically choose a mix of both.

The point is that the "softer" the state the more likely it will turn to extractive methods that involve citizens either minimally or voluntary or both.

This strategy is clearly visible in taxation policy in the Third World.

A good indicator of the "softness" of a state is the ratio of public revenue extracted from citizen incomes to public revenue collected at the country's ports.

The lower the ratio, the "softer" the state. The choice of mixes between "hard" and "soft" taxes can be seen as a concrete case of the larger choice between lower and higher yield-to-investment ratios.

Investment is the amount of coercion necessary to gather the tax. Yield is the amount of the tax thus gathered.

(Indirect rule, as in the tax-farming practices of the Dutch East India Company, would be an early colonial example of maximizing yield-to-investment ratios.

Direct taxation reinvested in welfare allocations under the Ethical Policy would be a late colonial illustration.

The shift between the two reflects the larger strengthening of what Harry Benda liked to call the Beamtenstaat, the administrative state.)

The trouble with a "hard" tax, as on personal incomes, is that it requires an extremly high investment in

[[[[p23]]]

[[[[p24]]]

Despite the ubiquity of gambling's use, its costs and benefits as a source of revenue are virtually unstudied.

To my limited knowledge, there are only two full-length sociological treatments of public gambling in English.

(With regards to Indonesia, Clifford Geertz has pointed out that Western visitors to Bali have ignored cockfighting in favor of the more serene aspects of the island's culture that confirm its "Bali Hai" image.

Nor is this selectivity of vision limited to to Westerners: India's current Five- Year Plan avoids all mention of lotteries despite their importance as a source of revenue in that country)

What are the cases for and against public gambling? A basic rationale in both hard and soft states is that people will gamble whether it is legal to do so or not and that the public interest might as well be served at the same time.

In hard states there is the additional argument that public gambling will provide tax relief, whereas in soft states it holds out the hope of high yield from low investment. The latter ratio can, in theory at least, help move a revenue-and compliance-poor government more rapidly along a developmental chain of economic, social and political reinvestment.

Arguments against gambling are legion. Gambling is said to involve related "vices" like drinking, whoring and crime in general, activities long condemned by most of the world's great religions.

Gambling taxes are said to be regressive because the bulk of bets are made by those least able to pay.

Gambling is said to deter the spirit of savings, to discourage hard work in favor of dreaming, to reinforce infantile desires for immediate satisfaction.

The battery of moral, economic and psychological arguments against gambling is impressive.

In soft states it is especially compelling insofar as governments in these countries face entrenched religions, widespread poverty and already weak propensities on the part of the citizenry to save.

Unfortunately, the normative proposition that gambling is morally wrong is untestable, whereas the empirical propositions about gambling's deleterious effects— with one exception

[[[[p25]]]

to be mentioned later on-have not been systematically tested. (Even if legalized gambling can be shown to undermine development, it remains an open question whether its illegal version would not no so even more.

[[[[p26]]]

Receipts exceeded expectations, however, and just a few months later, on January 15, 1968, this thin end of the wedge was widened to include a Chinese game called Hwa Hwee, translatable literally as the "Flower Organization.

By the time it was finally banned five months later, Hwa Hwee had transformed the city into a huge night gaming room of thousands upon thousands of players.

Governor Sadikin had been attracted to public gambling in the first place as a soft method of extraction. "This way I don't have to impose taxes on people," he told one interviewer.

A state lottery was already operating in Djakarta, but it had yielded only 60 million rupiah in 1967, or 5 per cent of the metropolitan budget for that year.

Sadikin realized that the lottery was not attracting big money. The big money was in Glodok, the financial heart of Djakarta,

and the Chinese weren't interested in a straightforward game of numbers without any specifically Chinese appeal.

What was needed was not any game but a game that would attract the Chinese. After the success of the Glodok casino, where various Chinese games were available, the Governor decided to try Hwa Hwee.

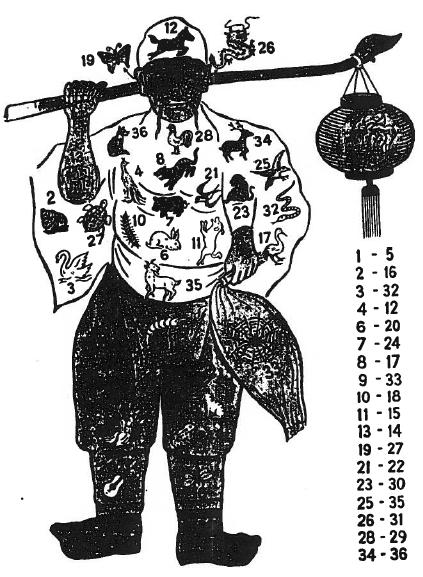

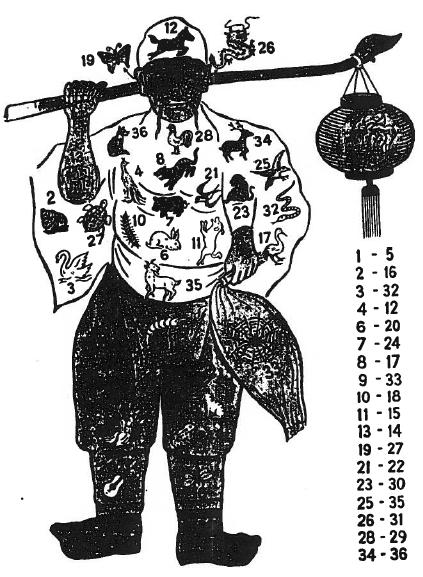

In Djakarta, the world of Hwa Hwee revolved around a 6 by 6 matrix of 36 squares. Each square contained three items: a human figure in traditional Chinese dress, an animal and a number from 1 to 36.

(In one or two squares, objects such as a guitar or two coffins replaced persons or animals.)

A player who bet on the winning square (person-animal-number) would receive 25 times his or her wager.

The minimum bet was 50 rupiah; there was no maximum bet. One could wager as many units of 50 rupiah, on the same cell or on any combination of cells, as one wished.

Although the principle of the game was thus similar to a kind of simplified roulette, Hwa Hwee proved a far more elaborate and captivating experience.

Roulette is essentially a game of numbers. Hwa Hwee is a picture-and-number game rooted in a richly connotative cultural tradition.

Although the origins of Hwa Hwee are obscure, it appears to have developed in southeastern China (Fukien

[[[p27]]]

and Kwantung) and spread from there through the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia.

The 36 persons are said to represent hostoric personalities martyred in the 12th century in the Kirin region in the defense of China against an invading barbarian tribe.

It is also conceivable, although this is pure speculation, that this band of heroes formed the original "flower organization" (flower = hero? ) after which the game is named.

The matching of an animal with each of these personages further enriched the historical, mythic and literary associations possible for each square in the diagram.

As in roulette, the bank's income in Hwa Hwee was the difference between the odds of coming up with a winning wager and the win- nings-to-wager payout ratio.

For example, in a coin-flipping game of heads or tails, the chances of guessing correctly the outcome or any given flip are 1:1 ("fifty-fifty"). If a correct guess pays 1:1 ("even money")-that is, if a winning bet doubles itself- then in the long run neither the person flipping and paying nor the person guessing and betting will be financially ahead or behind.

In European (single-zero) roulette, the player who places a bet en pleine atop one of the 37 available numbers (0 through 36) accepts odds of 36:1.

The winnings-to-wager ratio for that bet, however, is only 35:1. The difference of 1 (36 minus 35) is the bank's long-run margin of victory.

In Djakarta's Hwa Hwee, however, this margin, between betting odds of 35:1 and a payoff ratio of only 25:1, was exactly ten times greater than it is in European roulette.

Remembering this banker's advantage and the length and frequency of the game— one prolonged play daily seven days a week— it is not hard to see how even after a healthy cut for the banker, the metropolitan government could and did make some 50 million rupiah per month off Hwa Hwee.

Unlike roulette, the selection of the winning number was done in secret before the betting process began.

Official and unofficial clues circulating among players and potential players throughout a betting period nearly 12 hours long helped to build a tension to a

[[[[page28]]]]

fever pitch broken only by the final revelation of the winning square. Clues could refer to the number, the personage, or the animal in the winning square, or to any combination thereof.

Given the connotative richness of the game, the opportunities for allusive clue-making were limitless.

A typical day in the life of the game will suggest the powerful appeal of these tantalizingly ambiguous hints.

The epicenters of the Hwa Hwee phenomenon were two, both in the Chinese quarter: the organizing center (Pedjagalan) where the winning number was chosen and the nearby casino (Petak Sembilan) where it would be revealed.

About 11 am, in the secrecy of Pedjagalan headquarters and reportedly after certain ritual observances, the banker picked one number from 1 through 36, wrote it on a slip of paper, placed the paper in a cylindral tin container with a chain attached to its lid, closed the container and padlocked the lid.

The box was then wrapped in red paper. This secret selection was witnessed only by the banker himself and two "experts," all three of them Chinese and said to possess near-perfect knowledge of China's (Han) cultural tradition.

The two experts then carried the container a short distance to the casino.

A crowd had already gathered there to await their arrival. Inside the casino, a small cage hung beyond reach from the ceiling.

Preceded by a game official with a set of keys, the experts climbed the ladder. The cage had an outer and an inner door.

The keeper of the keys first opened the two locks on the outer door and the one lock on the inner door.

Requesting silence from the crowd, one of the experts ceremoniously hung the cylinder by its chain from the top of the cage and padlocked the chain in place.

Incense was burned, incantations were pronounced, and offerings of food were placed inside the cage before it was triple-locked again.

(There was no truth to the rumor that among these offerings was the severed head of a chicken— said to be a Chinese symbol of confusion.)

The key-keeper and one of the experts came down from the ladder.

[[[[page29]]]]

Clues were of three kinds. The first was the hand clue given in the morning by the expert still atop the ladder.

This clue usually consisted of a swift movement of the arm and fingers apparently taken from the repertoire of Chinese hand-fencing (silat),

a method of attack and defense well-known in Indonesia through Chinese dime novels and the assembly-line film swashbucklers of the inexhaustible Shaw Brothers of Singapore.

The expert would often have to repeat the gesture several times until the crowd had memorized it and could roughly reproduce it themselves.

Beyond the moming crowd, hand clues were not widely known. Some said they were deceptions, but others believed they were given to reward those who had assembled in the casino to witness the hanging of the number.

The second kind were written clues: proverbs, riddles, poems, pictures and number magic.

These clues came in theory from the experts as well, but there were so many written clues of all kinds in circulation that one could seldom distinguish official from unofficial ones.

Rumor clues were the third kind, passed by word of mouth, entirely unofficial and often related to a dream or some other personal experience.

Initially, given the intention of the metropolitan government to use the game to sop up some of the "hot money" of Glodok, Hwa Hwee was limited to Chinese players.

The casino was off limits to all but Chinese and foreigners.

Clues were published in the one Chinese-language daily paper, Harian Indonesia, where most Djakartans would not see them and could not read them if they did.

But as the popularity of the game spread to the non-Chinese population, so did the number and variety of clues written in Indonesian and of rumor clues passed among Indonesians.

Cards with different clues in Indonesian, all stamped "Official," were printed by overnight entrepreneurs trying to cash in on the craze.

Sheets began to circulate showing variously a monkey or a man with a numbered image from each Hwa Hwee square on each part of his body (see the illustration on Page 30).

His right ear, for example, was butterfly-19-general, while his left was dragon-

[[[[page30]]]]

A Sample Hwa Hwee Diagram

Note: The thicker the cloud of associations around each number-image, the more evenly spread the betting,

the better off the bank, and the easier it was to justify a clue that had apparently failed.

If the clue was 4 and the winning number was 24, for example, it could be pointed out that the correspondence "4— 12" really meant 4+1+2 = 7 and that 7 corresponded to 24,

[[[[page31]]]]

26-king. In another widely distributed diagram six concentric octagons with a yin-yang symbol in the middle provided a matrix in which the 36 game numbers were keyed to the seven days of the week.

Connections between even genuinely official clues and winning numbers were tenuous. One official clue read: "Went to the market with new clothes on. Met a beggar."

Even the gambler astute enough to recognize this as a reference to a fish— because a fish brought to market is still fresh and covered with shiny scales and attracts people who beg to buy it— would still have to choose between three different squares :

fish-1-devil, fish-29-priest, and fish-30-sailor.

On April 8th an official clue read : "A little body with a yellow head had a poisoned sticker. I taste roses everywhere."

At first, one might think this a bee (16). But on second thought, it could be a butterfly (19), because the butterfly was said to be a symbol for a famous prostitute (Lim Gin-giok).

But, in fact, the number that day turned out to be a reverse twist on the prostitute, namely, square 36 in which the nun (Tan On-sie) appears.

There were stories of the bank being broken, once through a too-obvious riddle about something with four and a half legs which turned out to be an elephant (13)

and once by a group of visiting Japanese businessmen sufficiently versed in Chinese literary and folk traditions to outsmart the experts at their own game.

Like so much else about Hwa Hwee, these stories may be apocryphal.

Rumors and wagers triggered one another in a chain reaction extending from Glodok outward and building to 1 1 pm, when official Hwa Hwee agents were required to close the betting and bring their unused receipts and collected bets back

[[[[p32]]]]

after the five locks had been opened, to withdraw from the tin cylinder the day's winning number. From the casino the news spread rapidly thoughout the city as winners and losers climbed into

betjaks, rode their bicycles or scooters, or walked home. Sitting on the roof of out apartement in the Senen-Kwitang area at a little past midnight, we could hear the chain of cries sweep by: "17! ... 17! . . . 17!" or whatever the winning number had been.

Thirteen hours after it had begun, the game had ended, only to be played again the next day.

That revenues from Hwa Hwee were spent in the public interest cannot be denied.

Gambling revenues, including income from the casino itself, the lottery and the slot machines, paid wholly or in large part for some 100 elementary schools, some 20 secondary schools, the Tjikini Cultural Center, the Banteng Bus Terminal, sports playgrounds, outpatient clinics, elevated pedestrian crosswalks, the widening of traffic-choked roads, even the renovation and reopening to the public of Djakarta's planetarium.

But eventually Hwa Hwee fell a victim of its own success.

Agents and subagents proliferated, setting up their tables or operating out of roadside cafe's all over the city, breaking the quarantine on Indonesian participation.

Many of these entrepreneurs did not bother r to depend on Pedjagalan at all, instead paying off winning bets with losing bets and pocketing the difference.

Not only were the lower strata in the kampongs— betjak drivers, prostitutes, bicycle tire repairmen, cigarette stall keepers— taking part on a larger and larger scale,

but many of their bets were being turned not into public benefits but private profits, a trend furthered by the decision of many self-appointed local agents to ignore the minimum 50-rupiah-bet rule and accept wagers as low as ringgit (2 1/2 rupiah).

However, most of the lurid rumors of Hwa Hwee-caused suicides, divorces, killings and bankruptcies that began to circulate orally and in the press were probably false.

Several of these rumors were ultimately proven incorrect or were retracted. A news item that the inflow of mentally disturbed persons into the Grogol asylum had

[[[[page34]]]]

dynamic, progressive governor enabled him to prolong the game as long as he did.

On June 15th the official Hwa Hwee operation closed down, although underground versions of the game cropped up in pres reports occasionally for some time therafter.

The demise of Hwa Hwee did not mean an end to gambling revenue.

On the contrary, Djakarta's estimated income from gambling for the 1970-71 fiscal year was more than double what it had been in the 1968 calendar year, the year of Hwa Hwee.

The metropolitan government has shown no signs of relinquishing this "unconventional" path to development, as the Governor likes to call it.

As we have seen, gambling as a source of public funds is not "unconventional" at all but has been adopted widely across time,

space and ideology in many if not most of the world's nations. However, as the Hwa Hwee experience illustrates , financially lucrative public gambling can have prohibitive social costs.

These costs must be included in any realistic estimate of the ratio of investment to net yield.

Ultimately, not only was the net yield from Hwa Hwee after subtracting its rising social cost not worth the continuation of the game,

but the investment in coercion and organization required to bring the game back under official control proved beyond the capacity of the metropolitan government.

That the concrete results yielded by Hwa Hwee have in turn yielded egitimacy for the government and thereby strengthened its capacity to govern is also clear, however.

The game has been all but forgotten, but the public facilities it provided remain.

Had the Governor invested Hwa Hwee profits in less visible or longer-term projects, their yield in public support would of course have been less.

What about the arguments against gambling?

In a careful survey of a random sample of more than 800 participants in Sweden's public soccer pool betting conducted in 1954, a number of critical assumptions about gambling were tested and found to be without empirical support.

Players in Sweden apparently gambled moderatly and in proportion to their incomes. They were not obsessive gamblers; their

[[[[page35]]]]

wagering did not make them apathetic toward work or family responsibilities.

Similarly, bettors as a group did not participate less in politics or in voluntary associations than non-bettors.

These findings may be of small comfort to Indonesians, however, for they may show only a kind of converse of the Hwa Hwee experience:

that public gambling is least pernicious in those societies that least need its extra revenue.

In this discussion we have emphasized the extraction and accumulation of resources, but their more equitable redistribution can also be an important goal of government.

On this latter point, the Swedish study strikes a note of caution.

Although Swedish soccer gambling was not found to be a regressive tax in the sense that the sizes of player wages and job incomes were inversely related, it was regressive in that the lower one's social class (by occupation and education), the more likely one's participation.

The bulk of bettors were those lower down in the social pyramid. Finding their chances for upward mobility blocked, they turned to gambling as a surrogate (and, save for the lucky few, unrealistic) channel of advancement.

This was especially true of lower-class elites, who plausibly had more contact with and more ambition to join the upper strata than did lower-class non-elites.

It would be premature to conclude from the Hwa Hwee juggernaut that using gambling as a source of revenue is unwise. Instead one might try to specify the kind of gambling most likely to maximize the ratio of investment to yield while minimizing the social cost. Casino table games, for example, are less regressive than lotteries.

In a casino there are fewer players with higher incomes who bet more; in a lottery there are thousands of players who be less but can also afford it less.

In a casino, furthermore, payout-to-odds differentials tend to be small to keep a more sophisticated clientele at the tables; in lotteries with mass participation ensured, they can become quite large.

Another advantage of the casino is that obviously low-income players can be refused entry at the door. By these standards, the social cost of Hwa Hwee was

[[[[page36]]]]

high: Gambling losses were inflicted regressively and by a large differential on increasingly massive numbers of gullible players who could not be kept out of the game.

other questions could be asked. psychologically, are skills games preferable to games of chance ? Are games that rest upon empirical situations preferable to games that encourage fantasy?

Soccer betting calls for knowledge of actual team performances rather than mystic number divination.

Brazil, for example, introduced soccer betting in 1970 hoping to drown out an illegal high-fantasy, lower- class animal game and to modernize the betting mentality by shifting it onto real-world skill criteria of achievement.

But games of blind chance are also more egalitarian— all players have equal probabilities of winning— and it is hard to disparage the escape into unreal worlds of people whose real world is as unattractive as that of the Djakarta poor or the favelados of Rio.

Then again, public gambling can also be seen as just another opiate (or methadone) administered by political elites to keep the masses "happy" and ignorant of their true condition.

Many other questions could be asked, for example, about the use or misuse of funds raised from gambling. Even assuming a socially harmless game, its profits may end up being spent on conveniences that disproportionately benefit the well-to-do (eg, road repairs to cut driving time).

But public gambling should at least be given the kind of careful study necessary to predict its likely dangers and limitations.

For the leaders of soft states like Indonesia are understandably not only interested in what they should do but also in what they can do. Desirable or not, gambling is at least an option .

NOTE 1. See Nechama Tec, Gambling in Sweden

Indonesia's elite: political culture and cultural politics by Donald K. Emmerson

So now the government has its revenue and Hwa Hwee has been banned.

Despite the ideological divisions separating groups, politics did not have to be a crusade or a game with only winners and losers.

But Usman was ready to abandon idea of cooperation based on mutual interest whenever he felt the ummat to be threatened.